Humanity has turned space into our most precarious ecosystem

There's an avalanche gathering above your head as you read these words. Not of snow or rock, but of human ambition. Twenty four thousand fragments of our ingenuity now circle Earth like a frenzied swarm of metallic bees, each bullet moving 10 times faster than a rifle shot. The mathematics governing their dance grows more terrifying by the month.

Imagine your city’s highway system suddenly being forced to accommodate 73% more vehicles in six years. Now imagine those cars are blindfolded, traveling at Mach 25, and solely relying on last minute shouts to avoid collisions. This is the reality we’ve constructed in low Earth orbit, a realm where humans now intervene less like careful planners and more like children stacking blocks while wearing mittens.

The numbers should jolt us awake. Satellite passes that once occurred every few minutes now happen every 22 seconds. A single constellation completes an avoidance maneuver three times every minute. We’re engineering a Rube Goldberg device of cosmic proportions where failure doesn’t simply mean losing expensive hardware, but potentially severing humanity’s connection to weather prediction, global communications, and emergency response systems.

What few appreciate is how orbital mechanics defies intuition. When two satellites collide at 17,500 mph, they don’t neatly explode like movie special effects. They disintegrate into thousands of fragments following the brutal laws of physics. A single collision between a defunct Russian satellite and operational Iridium craft in 2009 created over 2,300 trackable debris pieces, many still circling fifteen years later. Each becomes a shotgun shell aimed at other satellites, creating exponential risk that doesn’t dissipate quickly. At altitudes around 550 kilometers where Starlink operates, debris remains for decades, caught in an invisible game of bumper cars with active satellites.

We confront here a modern iteration of ancient patterns. The same shortsightedness that turned the open range into dust bowls and rivers into industrial sewers now threatens our orbital commons. Space was never empty, but we treated it as an infinite dumping ground, ignoring the growing web of mutual dependencies. Every GPS guided farmer, every pilot relying on satellite weather, every family video calling across continents participates in this fragile system.

Yet even as warnings mount, new satellites ascend weekly. The European Space Agency’s ClearSpace 1 mission designed to test debris removal remains underfunded, much like ocean cleanup initiatives that followed plastic’s irreversible spread. Our technological adolescence shows in how we address consequences only after they manifest catastrophically. We build brilliant solutions but lack the wisdom to prevent their secondary harms.

Satellite operators will rightly point to impressive collision avoidance systems. But complex systems invariably fail, and space offers no repair shops. The greatest threats might not come from predictable errors but black swan events like solar flares overwhelming electronics or cascading software failures in automated avoidance systems. History teaches that tightly coupled systems from nuclear plants to financial markets eventually experience catastrophic failures precisely because we engineer them not to.

Perhaps most worrying is the philosophical precedent. If we cannot manage 200 kilometers of orbital highways, what hope have we for future challenges like lunar industrialization or asteroid mining? The crowded sky becomes a test case for whether technological civilizations can develop planetary stewardship before resource exhaustion. Alien astronomers might measure our maturity not by radio signals but by whether we avoid self inflicted blindness from our own debris fields.

There’s an uncomfortable parallel to climate change here, but with crucial differences. Atmospheric pollution unfolds gradually while orbital collapse could accelerate violently once critical mass is reached. Imagine plastic waste that didn’t slowly choke sea life but actively spawned more waste whenever pieces touched. The Kessler Syndrome represents an environmental tipping point unlike any we’ve faced, where protective measures must operate flawlessly not for years but generations.

Curiously, the solution space reveals profound contradictions. The same companies contributing most to congestion now lead in developing debris mitigation technologies. Much like oil companies funding renewable research, their interests align with maintaining orbital usability while expanding operations. This creates moral hazard risks where profit driven entities control essential infrastructure while liabilities remain diffuse. Should private corporations bear responsibility for protecting orbital real estate all humanity depends on?

Some engineers propose radical solutions laser brooms to nudge debris, gossamer thin nets to capture fragments, even robotic graveyard tugs. But all require international coordination at a moment when geopolitical tensions strain space cooperation. The Artemis Accords governing lunar exploration show promising frameworks, yet low Earth orbit remains governed by outdated treaties better suited to 1960s technology.

Perhaps the hardest truth is accepting limits to growth. Orbital slots aren’t infinitely expandable, no matter how many improvement iterations we engineer. There comes a point where adding more satellites doesn’t linearly improve broadband coverage but exponentially increases systemic risk. Our economic models struggle with such thresholds, rewarding individual actors for maximizing launches while ignoring collective danger.

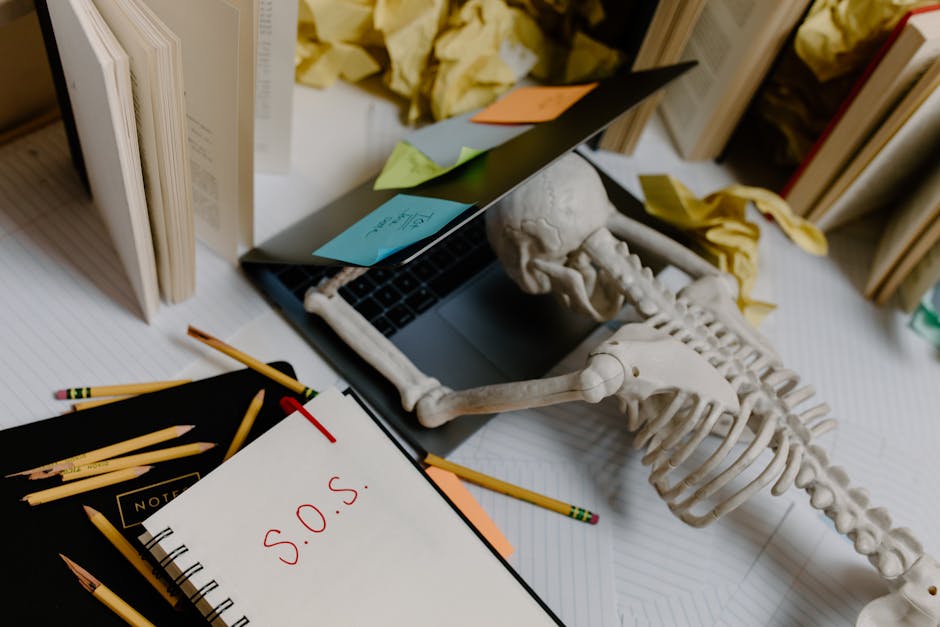

What remains is wonder buried beneath anxiety. Wonder that human minds conceived machines whirling perpetually beyond our atmosphere. Wonder that delicate instruments we built now guide lost hikers and monitor climate patterns. Yet this marvel risks being undone by thoughtless multiplication, our celestial architecture collapsing under its own weight if we ignore the warnings. The clock ticks not in days but actions. Three days from crisis leaves little time for apathy.

By David Coleman

By David Coleman