The original language of algorithms wants its due credit

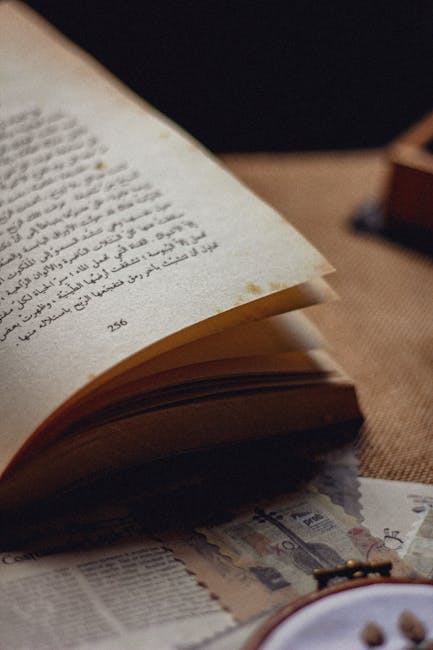

Consider the humble algorithm, that digital workhorse powering everything from social media feeds to stock trades. Few pause to contemplate why this mathematical term sounds suspiciously like the name Al Khwarizmi. Coincidence, or algorithmic appropriation? The ninth century Persian scholar Muhammad ibn Musa al Khwarizmi might be amused to discover his name now describes the very systems tracking your pizza deliveries.

Arabic contributions to English vocabulary form an intellectual heist epic spanning continents and centuries. The loot includes algebra from al jabr, alcohol from al kohwl, and even monsoon from mawsim. Each term carries receipts proving extensive cultural transactions that predate Silicon Valley by a millennium. Yet this linguistic paper trail rarely features in standard histories of science and commerce.

The transfer mechanism was straightforward. As traders moved goods along spice routes, scholars translated texts in Toledo’s melting pot, and empires rose and fell, words tagalong with material commodities. Sugar brought sukkar, cotton introduced qutn, and coffee imported qahwa. This lexical exchange wasn’t charity. It was the inevitable byproduct of civilizations cross pollinating through commerce and conquest.

North African dialects particularly influenced Spanish through eight centuries of Al Andalusian rule. Spanish then passed these words to English via European trade networks. The Arabic ta’rifa became Spanish tarifa, then English tariff. Zarafa transformed into Spanish girafa before anglicizing as giraffe. This linguistic game of telephone spanned generations, leaving many English speakers unaware of their vocabulary’s Middle Eastern roots.

Mathematics and astronomy contain especially dense clusters of Arabic derived terminology. Zenith descends from samt ar ra’s, meaning direction of the head. Nadir comes from nazir al samt, the opposite direction. The stars Altair and Deneb retain their Arabic names intact. Even basic terms like zero trace back through Italian zefiro to Arabic sifr, itself derived from Sanskrit. Every high school algebra student unwittingly pays linguistic tribute to Baghdad’s House of Wisdom.

This lexical migration reveals intriguing phonetic evolution. Arabic’s qaf sound posed challenges for European tongues. Words like qanun became canon in English and kanon in German. This wasn’t laziness but practicality. Languages adapt foreign sounds into their existing phonetic inventories, much as Arabic absorbed Persian vocab during the Abbasid Caliphate. The real surprise isn’t alteration but retention of core meanings across centuries.

Modern language pedagogy unintentionally obscures these connections. Students learn French derived terms are sophisticated, Latin ones technical, but Arabic imports rarely receive cultural context. We describe camels without mentioning jamal beauty, study chemistry without crediting al kimiya, and debate algorithms while erasing Al Khwarizmi. This selective acknowledgment subtly reinforces narratives of European exceptionalism.

The economic implications are tangible. Intellectual property debates rage over patents and copyrights while linguistic appropriation goes unchallenged. Imagine royalty fees for alcohol related vocabulary alone. Every bar receipt would require micro payments to Arabic linguists. While impractical, the thought experiment highlights how foundational these contributions remain. Modern finance depends on concepts like risk from Arabic risq and cheque from sakk.

Scientific communication’s dependence on Arab preserved knowledge remains particularly under sung. When Renaissance scholars rediscovered Greek mathematics and astronomy, they largely accessed them through Arabic translations. The very term algebra comes from al Khwarizmi’s foundational text Hisab al Jabr wal Muqabala. Decimal fractions, trigonometric functions, and astronomical tables all flowed through Arabic channels. Yet contemporary tech culture frames algorithms as purely Western innovations.

Globalization’s linguistic effects continue today, though directionality has shifted. Technology terms like internet and smartphone dominate modern Arabic dialects just as algorithmic terms once infiltrated English. But the inherent hierarchy remains. English borrowings signal modernity in Arabic speech while Arabic contributions to English are often historical footnotes. This imbalance reflects persistent power differentials in knowledge production and dissemination.

Educational reforms could address this cognitive dissonance. Mathematics curricula might note that solving for x continues a tradition begun in Baghdad. Literature courses could trace Shakespeare’s exotic vocabulary like assassin from hashshashin. Even preschools teaching animal names might mention that giraffes got their title via Arabic traders describing zarafa creatures. Such acknowledgments wouldn’t diminish other cultures achievements but place them in accurate context.

Technology offers new opportunities for linguistic transparency. Imagine translation apps tagging words with etymological histories or search engines visualizing semantic migration paths. Digital texts could hyperlink terms like coffee to their Arabic origins, creating awareness through everyday interactions. Such innovations might finally give Al Khwarizmi algorithmic justice.

The resistance to acknowledging these linguistic debts stems partly from discomfort with cultural interdependence. Western narratives often frame innovation as discrete breakthroughs rather than cumulative cross cultural exchanges. Yet penicillin emerged from mold observation, nuclear physics built on chemical discoveries, and even Einstein stood on non European shoulders. Denying Arabic’s contributions to science vocabulary perpetuates the myth of isolated genius.

Practical benefits accompany proper attribution. Understanding Arabic roots illuminates semantic connections. Algebra relates to bone setting through al jabr restoration of broken parts. Ghoul connects to stealing through root letters implying something that seizes. These poetic linkages deepen comprehension beyond rote memorization.

Nor are English Arabic interactions purely historical. Contemporary Arabized English flourishes in multicultural communities. Words like habibi enter mainstream usage through music and social media. Unlike older borrowings, these modern imports retain cultural markers rather than disguising origins. The pattern suggests increasing comfort with linguistic hybridity in the digital age.

Linguistic transparency could ease geopolitical tensions. Recognizing shared vocabulary might counteract stereotypes of civilizational clashes. If every algorithm nod acknowledged Al Khwarizmi and every coffee break honored its Arabic roots, interdependence would become undeniable. Tariffs derive from official announcements, algorithms from meticulous calculations, perhaps trade wars need similar etymological therapy.

For students struggling with algebra, consider this motivation. Each equation solved extends a tradition perfected in Damascus courtyards and Cordoba libraries when Europe was mired in medievalism. Those variables represent not just abstract numbers but history’s greatest knowledge transfer scheme. If nothing else, blame the Arabs for quadratic formula headaches. They documented it first.

The ultimate irony lies in English’s future trajectories. As machine translation advances, the language morphs into globalized pidgins. Already, Chinglish, Hinglish, and Arablish reshape communication. The next millennium might see English absorbing more Arabic vocabulary through technological osmosis. If Al Khwarizmi gets coding credit, perhaps future lexicons will document modern Middle Eastern contributions alongside ancient ones. The circle of linguistic life continues.

By Tracey Curl

By Tracey Curl