When cancer outsmarts chemo, science fights back with exploding water balloons

Imagine being a cancer cell. You're basically that obnoxious neighbor who annexed three yards to build a McMansion on stolen land. You multiply recklessly, ignore community zoning laws, and when authorities show up with eviction notices, you've already bribed the apoptosis cops to look the other way. For decades, oncologists have tried everything from chemotherapy wrecking balls to immunotherapy SWAT teams. But now, scientists discovered how to make tumors die from acute indigestion. Meet triaptosis, nature's answer to cellular gluttony.

The story begins with menadione, a molecule so unassuming it could be cast as the background potted plant in a vitamin commercial. This humble vitamin K cousin moonlights as an oxidizer, slipping past cancer's security systems like a janitor with a grudge. Inside the cell, it sabotages PIK3C3, a kinase protein that basically serves as the building superintendent for cellular storage units. PIK3C3 manages the endosomes, those sorting facilities that decide whether incoming molecules get recycled, stored, or tossed. Mess with this, and suddenly the cell transforms into a hoarder's garage during a Black Friday sale.

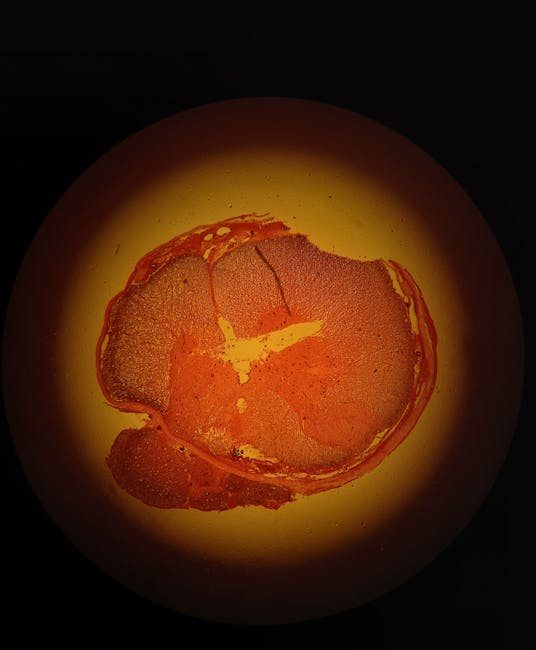

What happens next is equal parts biological tragedy and dark comedy. With the sorting machinery in disarray, vacuoles begin ballooning inside the cell like inflatable pool toys at a bachelor party. These aren't your average storage bubbles. They're massive, relentless space invaders that crowd out essential organelles until, as one researcher put it, the cell resembles a water balloon taped to a fountain. Eventually, the membrane can't take the pressure. Pop. The once fearsome cancer cell goes out with all the dignity of a stepped on ketchup packet.

Here's the beautiful part. While normal cells maintain their tidy, minimalist lifestyles, cancer cells tend to live like frat bros on a bender. Their rapid growth makes them overly reliant on those same endosomal systems now being weaponized against them. It's the cellular equivalent of targeting a burglar by electrifying their stolen flat screen. Poetic justice served with a side of oxidative stress.

The clinical implications are as bubbly as the mechanism itself. In mouse trials, oral menadione outperformed standard therapies against prostate cancer without turning test subjects into furry little pincushions of suffering. Safety and efficacy rarely ride the same elevator, but here they are, awkwardly avoiding eye contact while descending toward human trials.

Best of all, triaptosis doesn't play by the usual cell death rules. When cancers become resistant to apoptosis, the cellular version of faking their own deaths, doctors are left holding a metaphorical bail bondsman's notice. Triaptosis offers a completely different execution method, providing that satisfying click of a backup death switch resetting the game. It's the Chuck Norris roundhouse kick to cancer's diplomatic immunity.

But wait. There's more glitter on this science cupcake. Early signs suggest triaptosis might moonlight as an immune system hype man. Though still under investigation, researchers suspect those bursting cells release debris that screams, 'Hey immune cells, party over here!' If confirmed, combining triaptosis inducers with existing immunotherapies could turn frosty, unresponsive tumors into raging bonfires of immune activity. Cold tumors become hot targets faster than a microwaved burrito in a college dorm.

The road ahead sparkles with possibility. Scientists are now racing to develop smarter delivery systems, like nanoparticle FedEx trucks that drop menadione exclusively on cancer's doorstep. Others are exploring triaptosis combinations with existing therapies, essentially giving tumors the choice between a medieval flail or spontaneous balloonification. Even more intriguing are whispers that this mechanism might work beyond cancer in other diseases where cellular hoarding causes problems. Triaptosis could become the Marie Kondo of cell death pathways, sparking joy by annihilating anything that doesn't serve the organism.

Of course, nature loathes easy answers. As with all breakthrough therapies, questions linger. Will some cancers evolve inflatable sumo suits against vacuolization? Can we precisely gauge when a cell becomes overstuffed without harming healthy neighbors? How many biology students will accidentally make popcorn noises during lab experiments? These challenges notwithstanding, triaptosis represents that rarest of scientific treats: a fundamental new biological principle that doubles as a therapeutic sledgehammer.

In the grand biological opera, cell death mechanisms usually play supporting roles. Apoptosis is the dignified Shakespearean actor exiting stage left with a soliloquy. Necroptosis is the dramatic soprano clutching her pearls while collapsing onto a chaise lounge. Triaptosis? That's the slapstick clown getting pied, inflated, and rocketed into the orchestra pit. And for patients out of options, that clown might just be their hero.

What makes this discovery so deliciously hopeful isn't just its novelty. It's the reminder that even after decades of research, our bodies harbor secrets more fantastical than any sci fi plot. When existing tools fail, biology hands us a whoopee cushion and says, 'Try this.' Triaptosis doesn't just kill cancer cells. It does so with the whimsy of a Tom and Jerry cartoon, turning cellular biology into dark comedy gold. And in the fight against cancer, laughter might be the most potent medicine of all. Even if it sounds suspiciously like a balloon slowly inflating... inflating... pop.

By Nancy Reynolds

By Nancy Reynolds